Pre War Memories

Excerpts from a sequence of correspondence between Margaret Sanders, who was the Editor of the Journal of the Dilton Marsh Local History Society and Arthur J Porter who was living in Derbyshire. These letters and memoirs were written between 1994 and 1995.

18 November 1994

Dear Miss Sanders

With reference to your letter to my daughter dated 23 August 1994 regarding the Laundry and how it was run by my Aunts, I have tried to remember those days when I lived in the village between 1923 and 1936. The enclosed notes are the result – and in some ways I now feel that at the time I was not aware of the relationships between families – but I can now understand why I was more at home with my mother’s relations than those of my father. My grandmother Johnson was I believe born in 1863 and died 4 January 1936 buried in the same grave as her son Jack who died in l935, at the Baptist Church at Westbury Leigh. My mother was born 26 February 1883/84 and died 29 January 1937 buried in Barnstaple. My grandfather Porter died 17 May 1949 and is buried with his wife and daughter Ethel in Dilton churchyard. The Webb family were only known to me as a boy – Rose Webb lived at Stormore and her daughters Elsie, Flo and Ada lived at the laundry. I have no idea where they are buried but I do have a strong feeling that they belonged to the church at Dilton, so perhaps if you do find out anymore I should be very interested to hear from you. Meanwhile I hope you may find this account of interest and should very much like to know when your research is completed and published – I most certainly would appreciate seeing it in print. Please phone or write if you need clarification on what I have written.

Yours sincerely, (Signed) Arthur J Porter

Accompanying this letter are ten pages of typescript, the text as follows:-

Pre-War Memories of Dilton Marsh

Being born in the village gives one a very limited view of what went on when viewed from experiences in later life. My earliest memories must stem from the cottage which was in the middle of three which I believe originated from the weaving trade of the West country. These cottages were then known as Whitecroft Cottages because the hill alongside the lane called the Hollow was known locally as Whitecroft. Most houses at that time had extensive gardens in which most of the vegetables were grown, and in many cases additional produce could be gained from renting allotments. Wages were poor although some could take on out-work from the glove works at Westbury Leigh. Firewood could be collected from the surrounding woods and poaching took place for rabbits in Chalcot park.

The Laundry was worked by three sisters who were visited as Aunts because their mother and my grandmother were sisters. This laundry did the washing for Chalcot House which belonged to the squire of the manor. I can recall great wicker baskets of linen waiting for collection after being laundered entirely by hand. In the wash room was a very large wooden tub probably about 2 feet deep and 8 feet long with a cross section similar to an inverted triangle. Water was brought through to this room by means of a hand pump fixed either on the wall or to the end of the trough, also I remember a hand ringer fixed onto the other end of the trough. I almost forgot to mention that the water was taken from a stream fed from a spring. The main laundry room had a long ironing work top running the entire length of the room under the windows which faced the road. In the middle of this room was a cast iron stove standing on a metal tray to catch the cinders from the coke fuel. This stove stood on four metal legs within the tray. The four sides of the stove sloped inwards towards the top so that many flat irons could be heated at the same time – the irons resting on ledges at the top and bottom of the slope. In this same room were many wooden clothes horses which benefitted from the heat of the central stove. (Most of the drying was done on clothes lines in the garden).

Although electricity was in the village no electric irons were used prior to the outbreak of war, but I can recall light bulbs which hung from the roof. During the latter part of the war when I had returned to England I used to send my RAF collars to Elsie and Flo who were only too pleased to launder and return them starched to perfection. The other aunt was Ada who always had a small dog with her. She died during the late 60’s and when I last visited them in the village with my own family we were always made very welcome.

At the time of the last visit Flo was very ill in Warminster hospital and she could immediately see the likeness of my eldest daughter to my own mother. After Flo died Elsie went to the Hilcourt home in Trowbridge. We kept in touch until well into the 70’s but after a stroke she was unable to write to us so we never knew when she died. In those days it was natural to walk everywhere since motor cars simply did not exist in the village – even working families did not always have the use of a bicycle – so it became necessary to use footpaths across fields and farms to get to places quicker than keeping to roads and lanes.

An example of this would be to get to Westbury railway station from Dilton before the Halt was introduced in 1934 or thereabouts. This did have drawbacks however if a bull appeared when halfway across a field if running to catch a train to school. Retracing back to the main road to take the longest way invariably meant missing the train and turning up at school in Trowbridge late. The short cut across those fields – where adders or vipers could be found – to get to the station led to the start of what was known as the cinder path which ran alongside the railway embankment on the Westbury to Warminster line. The steep incline on this section meant the use of sometimes 3 engines to haul the long coal trains – 1 pulling and 2 bankers – hence the term locally used – “up the bank”.

Further “up the bank” between Tower Hill and the Half-mile road was a pumping station by the side of the down line from Warminster. I recall being allowed to descend into the bowels of this station and marvelled at the gleaming machinery I saw there. This pumping station provided water for the G.W.R. down at Westbury railway station during the heyday of the steam locomotives. The cinder path meant many stiles to be clambered over and steps down and up again alongside the bridges built over roads when the embankment was made. To avoid these obstacles many used to walk along the side of the rail track which was of course trespass. Where the railway branched to Frome and Warminster was the end of the coalyard – a huge stack of coal blocks many hundreds of yards (or so it seemed) around which the path led – past the engine sheds and the turntable before emerging at the end of the road near the station.

At the start of my schooling at Trowbridge Boys High School the long trek daily (including Saturdays as well!) was very tiring, but owing to the distance I did get a bus pass from the village to the station shortly before the Halt was provided. With the arrival of the Halt the journeys to school were more bearable. I was made aware that bullying of new boys was all par for the course. The two older boys who lived further up the village travelled on the same train and because the carriages did not always have a corridor there was no way of escape. Their favourite trick was to push me under the seats and stamp on them ensuring I was covered in dust – thus ruining my school blazer and cap. Any protest to the teachers would have resulted in even greater torture. Sometimes I would be put up on the luggage rack! However, when the diesel rail cars were introduced instead of the tank steam train with two carriages, the open plan seating eliminated any further incidents, and as far as I can recall ran from Warminster to Trowbridge. It was necessary to take sandwiches for packed lunch at school – after which we would sometimes go into Trowbridge to look at the shops.

There was also a World War tank in the centre of the Park. The railway system at Westbury was quite extensive and provided many hours of pleasure to observe the men in the shunting yards coupling and uncoupling wagons and it was also a train spotters paradise because of the number of trains passing through.

A favourite spot was a triangle of grass reached after crossing many different lines – both main line and shunting – where the lines to Frome branched off – and wait for the Cornish Riviera to come thundering through about mid-day from Paddington and drop its chute into the water troughs near what was locally known as the “Frome bend ”. To escape from the sheets of water which plumed out on each side of the tender was great fun – unless one got thoroughly drenched. The railway employed a great number of men and was regarded as a safe occupation to be in.

Around the early 1930’s the main line from Paddington ran through Westbury station itself and so the station had to be by-passed to avoid express trains slowing down for the “Frome bend”. This meant cutting across the old iron-ore mineholes which had been worked out and abandoned. These mineholes as I recall towards the end of the 20’s were filled with water which when frozen made excellent skating areas in the depths of winter.

My father still had his ice skates which he had brought back from Gloversville in New York state at the beginning of the Great War, and used to take me down there – I had to test the thickness of the ice for him – fortunately I never fell through. At that time the machinery and much of the heavy plant used in the open-cast mine workings was still there apparently intact even though abandoned. I never saw any ore being mined – but l believe there was some iron ore plant close to the railway station at Westbury – but I never knew what happened there. The cottage where I was brought up was rented property and the centre property belonged to a Mr Hillman.

My grandmothers cottage was the end one facing Whitecroft hill and she had 7 plots of ground used for her own use. Her cottage was at that time referred to as Vine Cottage since the whole front of the house was covered in a vine which bore green grapes. I have a vague feeling that Vine Cottage was connected in some way to someone named White who lived in a solitary house on Warminster road beyond half-mile road. The other cottage nearest the road was occupied by Bill Shergold who had been in the trenches in the Great War.

Facilities in those days were minimal as was to be expected in a village which had its roots based in the feudal system. There was an outside tap at the end of Grannies home with its lead pipe wrapped in sacking against winter frost. At the rear was a well which was covered over and I cannot recall it being used. There was a copper boiler for heating water in many homes. I recall the pantry was under the stairs and was very dark, so I bought a small battery, bell wire, bulb holder and a switch and fixed up a DIY light. Gran was very impressed – since we used oil lamps and candles at night. The plots adjacent to Granny’s house were also used by my father for his vegetables, and he vas very angry when the chickens belonging to the landlord got through the thorn hedge and ruined his cabbages and sprouts.

The upshot was we then went to live with Granny in her cottage until a house became available quite some time later in The Avenue. Since the cottage was close to the centre of the village every path and road was well known and some had their own local name.

The slight gradient from the village hall going towards the railway was referred to as “Little steep” – and was used to test out our home made trollies since very little traffic passed through to present any danger. Milk was carried in a milk float drawn by a horse and was ladled out of the churn into enamel billy cans which had a lid on. The only time I can recall seeing milk bottles was when milk in half pint bottles complete with cardboard lid was issued in the primary school during mid morning breaks. Sometimes skimmed milk could be fetched somewhat furtively from the farm – though at that time it was not legal to sell it.

A butchers van called regularly and I was very partial to a real faggot with its special taste of Wiltshire ingredients. The bakehouse was just around the corner where hot cottage loaves could be obtained. More often than not the soft sides of the loaf were too much of a temptation when I was sent to fetch one.

On a hot summer’s day the ice cream man with his tricycle might be tempted to push his heavy load from Westbury Leigh up either the main road or via Petticoat Lane into the village. There were two men working for Wall’s or Eldorado and the first one naturally made sales worth the effort.

A mobile fish and chip van also came round the village on some nights and was parked in an orchard in Petticoat Lane. There was no lack of things to occupy school children. A group of 3 or 4 boys would explore for miles around to see any unusual activities.

When roads were repaired the steam roller could be seen taking in water from the streams and proceed to tear up the surface with 3 or 4 teeth lowered into the tarmac. Then the exposed surface would be tarred and spread with stone chippings before being rolled down. Haymaking too was followed with interest as field mice and rabbits would bolt out from the path of the horse-drawn mowing machine.

I recall going back home once to make a Meccano model of the mower and waited weeks to buy a pair of bevel gears to operate the ‘blade’ – which I had to cut from a flattened-out cocoa tin. The stationary engine driving the escalator to load the hay onto the rick also kept us intrigued since it’s exhaust note was irregular being controlled by the momentum of the fly-wheel. Springtime would see games re-appear – whips and tops, skipping ropes for the girls, and iron hoops for rolling along.

The blacksmith near the railway bridge at the bottom of Tower Hill would make a hoop while we all watched – and would also repair them when the joint broke. Bows and arrows were made from ash and hazel from the woods. Kites (home made with help from my father) were also flown.

Picnics were taken to the park or at the foot of Whitecroft hill. Sometimes mother took us as far as “grassy slope” – along Wellhead Drove under the foothills of the Salisbury Plain – or farther still to the Westbury White Horse. To climb up and down the outline of the White Horse was quite difficult on the chalk slope as the chalk itself was very slippery. It was said that 26 people could sit side by side on the perimeter of the horse’s eye alone.

Once my sister was sliding down the slope and cut herself badly on a broken bottle lying in the long grass and had to be taken to hospital for stitches. Grassy slope was a favourite place to play since the steep slope was used to slide down on pram covers made from rexine. At the foot of the slope was another pumping station similar to that for the G.W.R. and yet another pumping station was at Upton Scudamore. Another hill we used was “Farmer’s Hill” near the laundry. This was fun when covered in snow to come down on home made sledges, or even old corrugated tin sheets.

During the summer holiday I would visit my grandfather near the Tannery and can still see him winding copper wire onto cardboard formers for coils. He made wireless sets and sometimes let me listen on his headphones. One day in 1936 he became very excited and asked me to listen. It was the sound of a machine gun firing. He had made a shortwave receiver and had picked up a transmission from a machine gun post during the Spanish Civil war. He was also very good at fretwork and made me a box with special divisions in to keep my Meccano pieces in. He also made the cabinets for the radio receivers. The power for the wireless set came from a re-chargeable accumulator since mains powered radio sets had not yet become commercially available. He was also clever at fretwork and made the cabinets for the radio receivers. Sometimes we would go swimming during the summer in a stream at Beckington above a weir – but it was always very cold.

One summer I spent some weeks at Warminster with a distant relation – I did not know it was because mother was expecting her 3rd child. The house was on the Frome road not far from Cley Hill – which of course I had to climb to the top. During that holiday I copied down the registration marks of the vehicles on that road and this taught me most of the index marks for Wiltshire, Bath and Bristol.

In the autumn we would go for conkers and this meant risking a chase from the gamekeeper in Chalcot woods. There were also sweet chestnut trees there too. Hazlenuts were collected from Blackdog Woods at the bottom of Stormore. Other excursions around the fields were to pick blackberries for jam making, gathering mushrooms hiding in the grass and I can also recall collecting hundreds of dandelion heads in full bloom for wine making. The best field for dandelions was a triangular shaped one at the top of The Hollow on the way to Old Dilton. Granny used a panchion covered with a muslin cloth and used to put raisins in as well. Elderberry wine was also made in a similar way.

Aeroplanes would attract a lot of attention as they were not very often seen, but if we heard one with a spluttering engine we would run to Old Dilton in the hope of seeing it land in a field known locally as Webb’s 90 acre field. Those early bi-planes usually had a skid in front of the landing wheels to stop the ’plane tipping up on it’s nose when landing on rough ground.

On another occasion we had a visit from Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus – a collection of aeroplanes for stunt flying and a large bi-plane for carrying passengers at five shillings a trip. An enormous sum for villagers in those days! The site where this event took place was on the same area where point-to-point meetings were held, and was between Dead Maids cross roads and Half-mile road off the Warminster road.

One particular event was during the 1935 Coronation. Beacons were lit all round the country – or so I believe – the chain of beacons included one at Dilton which was lit after the Westbury White Horse beacon was lit – with some difficulty I understand. The actual site of the Dilton beacon was in what was then 20 acre field overlooking the village and Chalcot park.

I can remember a large area of turf being removed from the slope above the iron railings and a tree trunk was planted in the centre for the main support. Branches and brushwood from the small copse on the side of the park were used to build up the beacon which made a huge blaze when lit. Sometimes we could hear the Army on manoevres going along the “top road” – i.e. past Chalcot house – with their light tanks and we would go to see them coming down Tower Hill and on through Westbury Leigh to Westbury before returning to the Salisbury Plain.

Occasionally one would shed it’s track and veer off into a hedge or wall before coming to rest. I had learnt to ride on my mother’s bicycle – a sit up and beg type – and can distinctly remember it was a “Coventry Eagle Flyer”. By sitting on the bottom bracket I could balance – but the handlebars were a little too high to reach comfortably – it also had a back-pedalling brake – making it difficult for me to stop. My next progression was to borrow my father’s bicycle – a “Rudge Whitworth” 23 inch frame, so this meant riding through the frame instead of astride. Perhaps it was because he could see the danger – he certainly did not approve – that I became the proud owner of a brand new bicycle – a “Hercules” with Sturmey-Archer 3-speed gears, chain guard and “North Road” handlebars.

Prior to owning my own bicycle our Sunday School teacher had borrowed bicycles for a group of boys in the class and took us on a long ride up onto the Salisbury Plain to visit Stonehenge. I learnt a lot from that ride – the tree where a highwayman had been hanged certainly helped to instill respect for law and order.

Sometime later after I had been confined to bed because of measles, I had to go to the Doctor’s at Westbury to sign off sick, and on the spur of the moment I decided to take the road onto the Plain to see Stonehenge again. In those days the roads were deserted – and as I was making my way across the Plain with no one in sight I was suddenly almost frightened out of my wits by the rat-tat-tat of a machinegun alongside me.

The Army used the Plain for manoevres and training and usually put up a red flag if this was to happen. I had not seen such a flag however so my shock was total. Two soldiers had seen me coming towards them and lay hidden in the ditch at the side of the road and waited until I was abreast of them before firing – they fell about laughing – but I do not think I have ever pedalled so fast in my life. The round trip to Stonehenge and back was about 50 miles – good training for later cycle rides from North Devon to Wiltshire (108 miles) for school holidays in 1937 – 8 – and 1939.

The Post Office was run by Mr. Bert Forward who I have reason to be grateful for when I was wrongly accused of trying to push the local tramp – who lived up in the woods – onto a bonfire. There was no truth in that accusation as the tramp was drunk and fell over without any help from me. Near the Post Office was the village cobbler – a Bill Gunstone who was a friendly fellow. Next to the Post Office was a motor garage with a hand cranked petrol pump selling R.O.P. petrol for less than one shilling per gallon. (ROP = Russian Oil Products).

Near the bakehouse I can remember a man living in a shed at the bottom of their garden since he was suffering from T.B.

I can also remember my sister being taken away in an ambulance because of either scarlet fever or diptheria. The lives of many people depended on the factories, and the hooter at the Tannery would sound at 8 AM and again at dinnertime. When the men came home for their mid-day meal it was quite a sight to see them rushing round the sharp corner near Granny’s cottage because some had to come from the glove works (Boulton’s) and get back again within the hour.

My father had been apprenticed in 1906 to Boulton’s and his indentures bound him to them for 5 years – but curiously it seems he had to pay some of his earnings to his employers after two or three years when he was allowed to go onto piece work. He had large hands – ideal for stretching the lovely skins before hand cutting the pattern from a template by hand shears. He told me that the design of the thumb gusset was patented by Boulton Bros. as the Boulton thumb. I assume he completed his apprenticeship about 1911 and must have soon emigrated to the U.S.A. in search of a more prosperous living. He came back to enlist as a soldier at the beginning of the Great War and was given an inscribed gold watch by his employers in the U.S.A. The watch is now in New Zealand held by my younger brother who has 3 boys – so perhaps the name of Porter may carry on when they marry. Father explained how the size of the gloves was determined by the span of one’s hand fully extended – from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the little finger – the result measured in inches = the glove size required. The skins mainly used were either pigskin (with distinctive hair marks), or sheep skin in tan shades. These dress gloves had three stitched seams along the back of the glove which were completed by home workers to pull the threads through to tie off. A dozen pairs (involving 12 ties per pair) would earn about three pennies per dozen. In 1936 father moved to Barnstaple to work for Dent and Allcroft who gave him the honour of cutting 3 pairs of white doe skin gloves – elbow length – for our Queen’s Coronation.

On his retirement early in the 60’s he was given just a simple letter thanking him for his years of service. He later carried on when called in to hand cut “special orders” until well after his 70th birthday. My grandfather was employed by Leigh Leather Works (Chas. Case and Sons) and retired from there as foreman. I understand the firm was originally based in Frome and moved to Westbury Leigh about the turn of the century.

The leather works was a busy place when I was a boy and the noise of the machinery driven by overhead belts for the buffing or polishing was deafening. The machines could be seen from the footpath which ran through the works from Dilton to Westbury Leigh. Grandfather had kept a square piece of pigskin from his first piece of tanned leather when the firm started production in Dilton and some 40 or so years later (1944 to be exact) – he was proud to show me that the leather was as supple as when first produced. I subsequently made him a tobacco pouch from it since I had learnt leatherwork whilst recuperating from illness in South Africa. Grandfather was buried in Dilton churchyard in 1949 having been cared for by my Aunty Ethel for 18 years following the death of my paternal grandmother of whom I do not have many distinct memories.

The two factories had their own cricket team and father and his brothers – Fred and Reg also played in the team. Father was a cuffy-handed bowler (left-handed) and was known to have achieved a hat trick on the field. I remember going to watch some matches with my sister Beryl and we used to take grandfather’s dog – a black labrador called “Chummy” along too. I never could get interested in the game so I pursued other activities.

On one occasion “Chummy” snapped at a wasp which had landed on Beryl’s lip when she was eating an ice cream. Unfortunately “Chummy” missed the wasp but bit through her top lip so she was rushed off to the hospital at Westbury for a stitch or two – she was otherwise O.K. Near the playing field was an area used for growing willow cane – the willow bushes were cropped back to the base each year to ensure vigorous new growth from the base of each clump. Since the area known as the Withy beds was surrounded by water it was not a place to play in.

The Tanyard houses were known as Boyer’s Terrace and were numbered 1 -12 almost opposite where the Halt was built. There was a path leading from the factory site to the gardens at the back of those houses and the field between the houses and the factory was used for grazing cattle. At the bottom of this field a large pit for the evil smelling liquid waste was created from clinker and ash and this pit kept getting bigger and eventually extended onto the gardens of the houses. The waste pit was continually built up and was high enough and the banks broad enough to carry the lorries round it’s top. I have been told that when a young lad fell into this pit that my grandfather rescued him from the slimy stinking mess. I believe this row of a dozen houses later became known as Penleigh Terrace – and after the war were re-named Fairwood Road and re-numbered 10 -22 when the field was built on. My grandfather lived at No.l (nearest the factory) and Uncle Fred and Aunty Doris at No. 11 (original numbers).

The inhabitants of the village were greatly influenced by which church or chapel they attended. I can only speak of the influence of the Baptist chapel, although the Methodist chapel at Penknap was equally attended.

Sunday school teachers did a good deal to encourage good citizenship and the Minister used to let us use his snooker or pool table in the Manse opposite the “PHIPPS ARMS”. The annual Sunday school outings were well organized for whole families and the places visited were Weymouth, Bournemouth and Weston-Super-Mare.

Granny would still walk to the Baptist chapel until just before she died in 1936. When she had a whitloe on her right forefinger she had to go to Westbury Cottage Hospital and the last two joints of that finger were amputated. (No antibiotics were then available). She was known as Polly to her close friends and Mrs. Pearce looked after her in her last illness before she died.

I had been living with Gran betveen 1934 – 1935 and her death left me devasted. At that time my own mother was ill and a year later died in January 1937 – only a month after we had moved to Barnstaple where Dad had moved to to continue in his trade as a glove cutter. My younger brother Bob was then brought up by Aunty Ethel from 1937 and through the war years until 1948.

One event remains in my memory and it was early in the 1930’s. Almost opposite where the Laundry stands was a field where a large marquee appeared and for a week it was packed when evangelical meetings were held. I went with Gran and when the marquee moved onto a site at Chapmanslade I went there again.

The social standing was roughly split by location of homes. Those living at the top end of the village nearest to the railway appeared to be fairly well off – whereas those farther down towards Stormore lived very modestly. The Police house was situated in the Crescent and about 1936 new rented houses were built in The Avenue. Father was allocated No. 1 and Mr. Toop No. 2. The large gardens at the rear were well cultivated once the turf had been removed and rotted down. The stream between the Crescent and the Avenue ran alongside our garden which backed onto fields adjacent to the Park.

There were two ponds at the back of the village with iron railings running through the centre of them and we used to see frogspawn in the Spring and sometimes see orange coloured newts. At the rear of the Laundry there was a small wood which we knew as The Firs. Between the Laundry and The Firs a house was occupied by someone called Carpenter.

Occasionally some gypsies would camp near the GWR pumping station above Old Dilton. I can only remember one pedlar visiting the village on his bicycle with a suitcase on the rear carrier. I did not know what he was selling but can recall that he was a foreigner because of his dark skin and strange turban which we had not seen before.

Schooling started at a very early age – from age 3 upwards – in either the Church school near the Church or at the British school farther down the village opposite what was known as the Laundry.

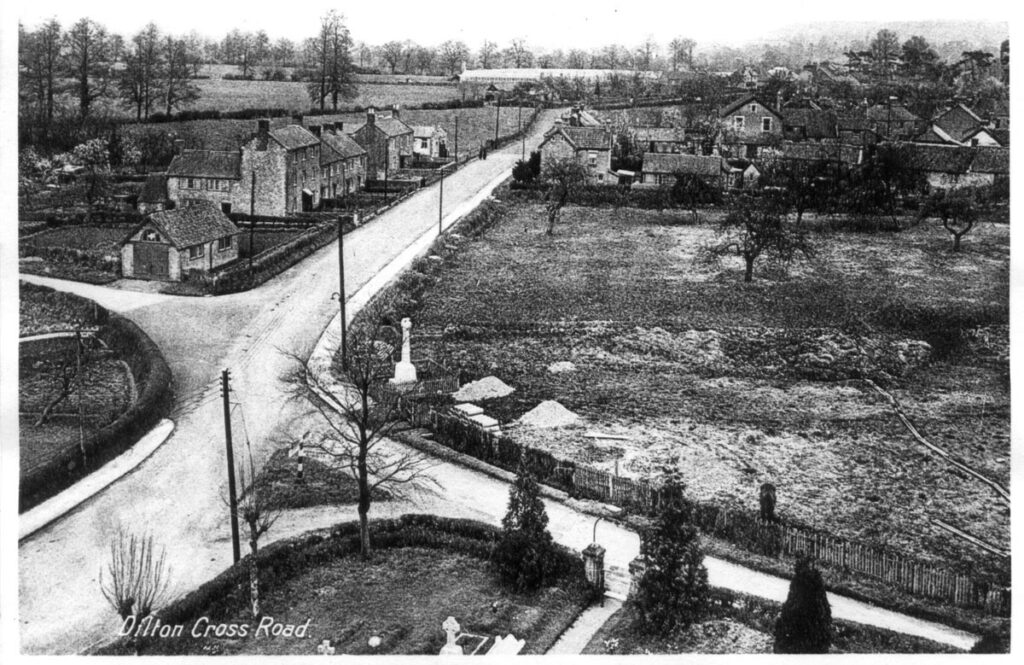

When I attended school in the village I had to walk the distance from Whitecroft (pronounced Whitekert) – around the orchard which stood between the cottages and the War memorial. The signpost then stood on a triangle of grass separated from the church wall. Both my brother and I recall being very scared in the infants class at the British school as the boiler was in the same room and the header tank very often bubbled so fiercely that drops of hot water would fall onto those in the first row or two of the class. Very frightening it was. However school was taken seriously and anyone misbehaving could expect a few strokes of the cane.

Once I received punishment I did not deserve – I had been accused of vandalising a blackbirds’ nest with young chicks in – by another boy who lived in Stormore and attended the Church school. There was never any truth in that but I had the cane against which I rebelled.

The church at Old Dilton was not used as far as I remember, and we often passed by on the way home from Sunday school by following the stream at the bottom of Westbury Leigh to go past the mill with it’s water wheel.

One Spring Sunday a group of us took this route, but because there were floods to see after the winter snows, so we continued up to half-mile road, then onto the Warminster road towards Dead Maids’ cross roads, then past Chalcot House and down the Hollow to get home – rather wet and muddy.

Chalcot house did not welcome visitors from the village – but I can vaguely remember a garden party being held at which some villagers were allowed to go to, and it was the only time I ever saw the grounds in front of the house.

The local bus service was operated by the Western National bus company and terminated at the Green where the road forked to Stormore or Frome.

A path from Gran’s cottage went through some allotments at the end of which was a stile for the path to continue alongside an orchard before emerging at the foot of Whitecroft hill. There was usually a small spring welling up from the ground at that point which was led into the ditch by the side of the path. The footpath continued up over the field and across cultivated land before ending on the road at the top of Tower Hill. In the corner of the field at the foot of Whitecroft and next to the orchard was a pond next to the hedge separating the field from the Hollow and by crossing the lane we called the Hollow there was an area we often went to for picnics in the shade of a row of huge elm trees – one of which had been uprooted in a storm.

(Signed AP)

Letter from Margaret Sanders to Arthur Porter acknowledging receipt of his memoirs 21st November, 1994

Dear Mr. Porter,

Thank you so very much for your letter of 18th November, and the really wonderful set of notes on your memories of living in Dilton. I have not yet done the necessary research on the graves of your family which you mention, but shall be doing so as soon as possible. I feel that your notes are such a lovely record that I would like to use them, if you agree, in the section of my history which consists of reminiscences by some of the older members of the village.

Recently our local paper has been running a series of such recollections, and one the other day was of a Londoner who came to Dilton as en evacuee during the War. This was most helpful as it is a period about which, so far, I have not much information. I saw Aileen the other day, and she said that Mrs. Porter who lives in Boyers Terrece was still very lively and would be glad of a visit, so I shall be arranging to go and see her. In some of my research, I found in the Church Accounts payments being made to Hannah Webb for laundering the surplices from 1870 through to 1904, when the payments start being made to Rosa Webb until 1917.

Do you think that Hannah was the mother of Rosa? After 1917 the washing seems to have been done by a Mrs. Price, and in 1922 by Mrs. Potter but there is nothing to show that these two ladies were actually connected with the Old Laundry. One of the things which has been very helpful in your notes is that you have described the footpaths, etc. so well.

You may be interested to know that the footpath from your Grandmother’s cottage “through the allotments and continuing alongside an orchard” is still there, and my house is one of four built on that orchard, with gardens which run right down to the footpath. The spring certainly still exists, as it was very evident in 1976 during the drought when all the field was brown except for the small patch round the spring. The footpath also tends to become a small river in the very wet weather. The pond next to the hedge has, unfortunately, been filled in.

Your references (several times) to the Half-Mile Road are very interesting, as I have not heard of this before. Which road is this? Is it the road from Old Dilton through to the Warminster/Bath road? The field you mention as being good for dandelions has long since been ploughed up, but the field at the top of the Hollow on the right-hand side (i. e. in the corner of The Hollow and the ‘top road’ to Dead Maids) is still marvellous for dandelions, and, like you, I go there each year to pick them for my own dandelion wine. I can be sure that in a big field like that they will not be polluted by cars, as would be ones on road verges.

We are often disturbed by ‘planes nowadays! The big Hercules from Lyneham practice dropping over at Keevil airfield, and the approach line is right over my house at what seems to be roof level!!! They are so big and make such a noise, that it is rather frightening. We also get a lot of helicopters when there are army exercises on the M.O.D. training grounds up on the Downs behind Westbury and Bratton. Very many thanks, once again, for your delightful reminiscences of your childhood in Dilton Marsh.

Yours sincerely, Margaret Sanders