View North from Church Tower

Dilton Marsh Water and Sewerage

1. Water and Sewerage before 1970

The village of Dilton Marsh is situated at the extreme west of the county of Wiltshire on the Somerset border. It is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southwest of the town of Westbury so called it is said, because it is on the west side of Salisbury Plain. Most of Dilton Marsh soil is clay except for the southeast corner, which touches Salisbury Plain and tends to be chalk. The village is aptly named Dilton Marsh as originally much of it is low lying drained marshland with the highest point reaching just over 250feet.

Dilton Marsh did not have piped water until 1923 and the majority of properties in the village were not on the main drainage/sewerage system until the early1970s. Prior to 1831 throughout Britain, there was little concern as to how sewerage was dealt with. That year some 32,000 people died of cholera and this served as a major ‘wake up call.’ Of note, the system of sewers is called sewerage or sewerage system in British English and sewage system or sewer system in American English.

In the summer of 1832, Orders in Wiltshire Council advocated the setting up of Boards of Health and letters to this effect were sent to towns throughout the county. Although some towns were more proactive than others, once the threat of cholera receded so did most interest. The next major outbreak of cholera was in 1849 when Wiltshire recorded 320 deaths from the disease and it was assumed that the disease was transmitted by bad air. However John Snow (1813-1858), a London-based physician showed that cholera was a water-borne infection and his research of a third outbreak in 1854 ratified his theory.

At this time, Sir Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890) was the secretary to the English Poor Law Commissioners. Basing his arguments on John Snow’s findings, he classified the country’s worst areas for cholera. He rated Salisbury, Wiltshire, as having one of the worst reputations in the country for ill health and that there was a notable lack of cleanliness while household drains emptied into open water channels leading directly into the River Avon. More affluent homes in Salisbury, it was reported, did have cesspits but many were overflowing or seeping into the soil that was so waterlogged with excreta that most cellars in the vicinity were smelly and wet with damp walls. Sanitary improvements were suggested but throughout the city opposition was strong. Eventually, in 1853 sanitary improvements began. These included the digging of deep wells and the laying of glazed pipes and brick sewers to carry sewerage and water away from the city into the River Avon. Subsequently the death rate dropped. Although the opposition became muted, the general resentment persisted such that throughout the rest of Wiltshire the dumping of crude sewerage into local rivers and streams remained the norm.

Nationally, reforms continued and the 1872 Public Health Act created urban and rural sanitary authorities, which employed a medical officer of health and an inspector of nuisances but was paid for by local councils. Work was advised but due to costs, this was reluctantly carried out as it frequently caused hostility between neighbours or neighbouring councils. Nonetheless, concern was slowly mounting and standpipes were erected to provide clean water. In the neighbourhood of Church Street and Market Square, Westbury, some households even had piped water brought by force of gravity from the springs at the foot of the Downs to the east of the town. For the rest of the town and surrounding villages crude sewerage and effluents from factories and homes were consigned into rivers and streams with drinking water sourced from wells frequently fed by these same streams.

From 1835, starting with the Municipal Corporations Act of that year, there followed a series of Corporation Acts that reformed the country’s local governments by establishing uniform municipal boroughs. The final Municipal Corporations Act in 1885 led to the dissolution of Westbury’s Corporation the following year. In consequence, Westbury’s corporate property was vested in the Town Trustees and they in turn formed a parish council but no record of its activities has survived. Albeit in 1837, Westbury public baths in Church Street were presented to the town by William Henry Laverton (1845-1935), who owned the now designated Grade II Listed cloth producing Angel Mill. This was on 11 May 1887, the day of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. They were opened to the public on 24 May. The water was pumped from a spring at the Hollow in Dilton Marsh.

The more populous Dilton Marsh, due to its thriving weaving industry, had superseded the nearby medieval hamlet of Dilton in importance in 1808. That year, the Westbury Enclosure Award was signed and the weavers were encouraged to buy and improve the hovels in which they lived. Many could not afford to do this but the local gentry, notably the Phipps family who lived at Chalcot House, soon owned most of the cottages in the village. During the 19th century the home weaving industry gradually gave way to factory produced cloth and up until World War II nearly everyone in the village rented their homes from the Phipps family.

In 1894, Bratton with Dilton Marsh became separate civil parishes and two years later in 1896, Heywood also became a civil parish. This was followed in 1899, by the creation of Westbury parish as an urban district with a council of 12 members. The council’s first meeting was held at the Laverton Institute on 4 October 1899, when besides a clerk and a treasurer, a sanitary inspector, and a medical officer were appointed. A Finance and a General Purposes committee was immediately set up and among the first matters of concern was the supply of water to properties in the town of Westbury that did not receive piped water from the spring at the Hollow. Considerable debate took place as to whether to pipe water from other springs or the cheaper option of sinking another well. The latter was chosen and it was agreed to employ a water diviner with a view to sinking another well in the town. However, a few days later a boy fell to his death down one of the town’s existing wells so the decision was made for a Westbury municipal water works.

The Westbury municipal water works however did not include the devolved villages of Bratton, Dilton Marsh and Heywood. This gave rise to a public outcry particularly from the fast growing village of Dilton Marsh though within a year the Westbury and Dilton Marsh Joint Water Committee had been formed. The committee was made up of representatives from Westbury and all the rural villages. In 1901 a pumping station along the Bratton road was opened with a reservoir at the junction of New Town and Long River. However, when these improvements were paid for there was very little money remaining for the lying of pipes! Thus, it was agreed that water pipes would be laid on an adhoc basis as finances allowed.

As for the provision of a sewerage system, Westbury and district’s history in the early twentieth century, along with the lack of piped fresh water to people’s homes and inadequate arrangements for rubbish disposal, is littered with reports of sewerage inadequacy. In 1907 it was reported that much of Westbury’s sewerage, including that from the factories, was discharged in its crude state into ditches on the north side of the town and thence it made its way into the River Biss. Sewerage from Westbury Leigh found its way into the River Biss by way of Penleigh while Dilton Marsh’s sewerage was either dumped on fields or emptied into the many streams. These streams fed the wells from which the village drinking water was drawn. The Wiltshire Medical Officer of Health was so appalled by this state of affairs that he not only made his views felt, he added that the council should at least introduce some form of rubbish disposal service. As dealing with rubbish would cost less than the provision of an adequate sewerage system, it was given priority. Satisfied with the result of the disposal of the town’s rubbish, in 1911 Westbury Council prepared a report on a proposed sewerage scheme but as this was estimated to cost £13,000, it was deferred. As for villages, it was agreed that both the drinking water and sewerage disposal systems had stood the test of time and therefore did not need expensive updating!

Within three years Britain was at War and due to the proximity of Salisbury Plain, pressure was put on Westbury and local villages to provide accommodation for troops. This, in turn resulted in a demand on Westbury and Dilton Marsh Joint Water Committee to bring up to the military, basic standard water and sewerage and waste disposal facilities. Financial help was sought from central government and with the added provision of military manpower, work was started. However, as the World War I continued and the shortage of men on the European battlegrounds escalated, work petered out so very little was actually achieved.

Following the War the country’s economy shrank but in 1922 Westbury and Dilton Marsh Joint Water Committee agreed to build a sewerage works at Frogmore for Westbury town only. It was also agreed, without any discussion with the Phipps family, that the Dilton Marsh area could rely on the family to provide the sewerage needs of the village. At the time the owner of Chalcot House, Charles Bathurst Hele Phipps (1899-1990) and Lady Sybil (1889-1960) had four small children such that they spent little time at Dilton Marsh leaving the management of their property to their steward. However, following discussion with Charles Phipps, in the 1920s, it was agreed that the steward would arrange to build a sewerage pumping station in St Mary’s Lane. This was for Chalcot House estate and any owner or occupier of any of the Dilton Marsh properties that were prepared to pay to be connected. A number of wealthy Dilton Marsh residents were connected and in 1936 the Public Health Act expanded the right of owners or occupiers of any premises to have a drain or sewer connection with a public sewer of the local authority as long as they were prepared to pay. By this time Wiltshire Council owned the St Mary’s Lane sewerage works but most ordinary occupants of properties in Dilton Marsh properties could not afford pay to be connected to the sewerage facility and so continued to deal with sewerage as they always had.

This situation was not unique to Dilton Marsh nor was the continued lack of the provision of fresh water. In 1925 a national survey was published that graphically described the plight of English villages due to the lack of fresh water. This led to the 1929 Local Government Act, which made provisions for county councils to ameliorate the problem. The Minister of Health, Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940), urged Wiltshire Council to undertake surveys. Following this directive, many local councils and villages applied to the county council for loans to make provisions. This included Westbury but not Dilton Marsh, because Phipps did not approve. Instead, the Phipps estate offered to supply piped fresh water to villagers’ homes with the right to turn it off one day a year of their choosing. The deal was rejected by the Westbury and Dilton Marsh Joint Water Committee who said that they would build a second pumping station at Wellhead for the use by Dilton Marsh residents. The pumping station opened in 1929 but the Joint Water Committee could not afford to lay pipes that would connect Dilton Marsh residents. Complaints were made to the County Council to which in 1934 they responded by stating that they would provide assistance for public standpipes ‘except where premises were efficiently drained or the means of water supply was directly approved by the county medical officer!’

Miss Elsie Webb lived at 181 High Street (now 88 The Old Laundry) and according to Kelly’s directory for 1939 she did the laundry for Chalcot House in her own home, which she rented from the Phipps. Therefore, her cottage was connected to the main water supply but she was only allowed to use the water for Chalcot House’s dirty washing! Where her own water came from is unclear for although a standpipe on the High Street, close to where Miss Webb lived is shown on an OS map of 1901, it is not shown on the 1924 edition. Of note, Miss Webb and her predecessors, Mrs Davies and Annie Phillips, physically washed the Chalcot laundry using dolly tubs and mangles and hung it out to dry using old fashion pegs.

The management of water resources, the control of flooding, the supply of water and the treatment of sewerage were generally based on archaic uncoordinated statutes and were of no concern to any authority in Dilton Marsh. Typically, the Statute of Sewers, passed by King Henry VIII in 1531 regulated land drainage. The basic Act had been augmented by a succession of Acts which, in essence, concluded that those who directly benefited from drainage works should be expected to pay for them. Following complaints, the 1927 Royal Commission on Land Drainage in England and Wales removed the earlier Acts and this was followed by the 1930 Land Drainage Act which was aimed at eventually creating an integrated management structure for water. One of its main tasks was to ensure that the drainage of low-lying land such as Dilton Marsh could be managed effectively by setting up catchment boards. However, the Act was put on hold due to the economic climate of the 1930s, World War II and post-war economic demands. So the problem in Dilton Marsh remained.

In 1944 it was found that 70% of rural households and nearly 100% of urban households in England and Wales had piped water supplies. For the remaining 30% of rural properties, the Rural Water Supplies and Sewerage Act came into force making the provision of piped water supplies obligatory. In 1950 the Wiltshire medical officer of health reported that ‘several schemes had already been completed and others were in progress. That many miles of pipes had been laid and a supply was nearer to many villages.’ but not Dilton Marsh. In 1959-1960 the Westbury sewerage works was expanded and modernised to meet the demand of new housing in the town that had taken place since 1922 but again did not include Dilton Marsh. Following a public outcry in Dilton Marsh it was agreed that a public inquiry would be held by the Westbury and Dilton Marsh Joint Water Committee. However, shortly after, its functions were taken over by the West Wiltshire Water Board and the latter were obliged to hold the inquiry.

This took place in 1961 when it was vociferously stated that the village reeked of raw sewerage and that this was due to the open ditches around the village into which human sewerage was discharged. At that time the population of Dilton Marsh was 1,320. A survey carried out the following year, reported there was a sewerage pumping station in St Mary’s Lane but only for those who could afford to pay for the connecting pipework. Dilton Marsh had 22 council houses that were connected to a small disposal plant. For the remaining properties, 37% of homes had chemical closets, 32% had septic tanks – the effluent from which was emptied into open ditches while the 6% of households with cesspits and the 11% of households that used brick pit toilets also emptied into open ditches. The remaining 14% of households relied on buckets (privies) in the garden the contents of which were emptied directly onto the land.

A scheme, approved by the then Ministry of Housing, proposed to extend the main sewerage system and re-siting the sewerage pumping station (SPS) at Penknap from the adjacent Apple Tree Inn (now Bridge House). In 1963 West Wiltshire Water Board acquired land from the Chalcot Estate on Clivey Hill for a Sewerage Treatment Works. That same year the St. Mary’s Lane SPS was acquired along with the Penknap SPS from the Apple Tree Inn. That year the Water Resources Act based on the Land Drainage Act 1930 was at last enacted. This created River Authorities and the Water Resources Board. The first were responsible for conservation, re-distribution and augmentation of water resources in their area while the Water Resources Board was set up to ensure that water resources were used properly in their area and included river boards that had been created under the River Boards Act of 1948. Although the latter did not integrate the provision of public water supply into the overall management of water resources, it did introduce a system of charges and licences for water abstraction. This enabled the river authorities to allocate water to potential users and the Water Resources Management was entrusted to 29 river authorities created in 1965. Their responsibilities included water conservation, land drainage, fisheries, control of river pollution and, in some cases, navigation.

By 1966, 355 Dilton Marsh properties were connected to the main sewer system though most properties owned by the Chalcot Estate were not. Apparently, only when Chalcot Estate cottages were advertised for sale were they connected to the main drainage system! Taking those homes without connections to the main sewerage system into account and the possibility of more homes being built in Dilton Marsh, it was estimated that the population of the village would increase to 1,500 and this should be taken into account when building the new Sewerage Treatment Works. At that time, the water authority revenues were not ring fenced from the general local authority budget therefore, local authorities could determine whether income should be used for operation and improvement of water services or absorbed into the general local authority budget. Although this was of concern, the main argument was the size of the Dilton Marsh Sewerage Treatment Works.

Some Wiltshire County councillors expressed concern over the cost and opted for reducing new housing planning permission while others pointed out that the amount of money they received from the Rating system would increase when more houses were built. In the end it was proposed that the size would include an estimated increase in population due to new house building and would cost an estimated £60,100. Nationally, from the 1950s, Britain experienced a modest current account surplus on the Balance of Payments then, in 1963 the visible trade balance declined and there was a deficit on the current account that was to last until 1967, the year the £ was famously devalued. Local Authorities were forced to reign in their spending with large capital projects requiring government approval. Planning approval of the larger Dilton Marsh Sewerage Treatment Works was sought and given by Wiltshire County Council just prior to the 1970 General Election. The project was then sent to central government for approval and was given! Work started straight away and the Dilton Marsh Sewerage Treatment Works was completed in the early 1970s!

2. Dilton Marsh Sewerage Treatment Works

Technically, there are three types of sewerage: domestic or sanitary sewerage, industrial sewerage, and storm sewerage. Sanitary sewerage carries used (grey) water from homes, industrial sewerage from manufacturing or chemical processes while storm sewerage is run off from precipitation that is collected in a system of pipes or open channels. The Dilton Marsh Sewerage Treatment Works (DMSTW) built in the early 1970s is combined, that is the sewers that feed it typically consist of large-diameter pipes or culverts that carry a mixture of both domestic and storm sewerage. Due to national legislation, housing developments built since 1995 are legally obliged to be designed to keep domestic and storm sewerage separate.

By rule of thumb, the maximum amount of sewerage that can go through DMSTW is 13.1 litres per second (47,160 litres = 47.16 tonnes per hour) in storm conditions. This is approximately 3 times the amount that usually passes through in dry conditions when the contents are mostly domestic sewerage. Domestic sewerage is slightly more than 99.9 percent water by weight and contains a wide variety of dissolved and suspended impurities. The nature of these impurities and the large volumes of sewerage in which they are carried make disposal a significant technical problem. Although the main impurities are putrescible, that is liable to decay, for instance organic materials and plant nutrients. Domestic sewerage also contains many millions of micro-organisms per litre most of which are coliform bacteria from the human intestinal tract but there are also likely to be other microbes.

The DM sewerage system includes laterals, submains, interceptors and in places, force mains. Laterals are the smallest sewers in the network and tend only to be used for individual house connections, usually not less than 200 mm (8 inches) in diameter. They carry sewerage by gravity into larger submains, or collector sewers. Submains feed into a main interceptor or trunk line, which carries sewerage to the treatment plant. However, as DMSTW is located partway up Clivey Hill, sewerage from lower lying properties has to be ‘forced’, that is pumped up the incline from the sewerage pumping station at the junction of Clearwood and Clivey Hill.

When the combined sewerage arrives at the DMSTW it is cleared of large objects that may block or damage the rest of the treatment facility. Such objects may include nappies, wet wipes, sanitary items, undergarments, soft toys and other objects that consumers have managed to flush down their loos. The sewerage then passes to Screening where it is goes through 6-10 mesh, in other words this is six to ten little squares of mesh across one linear inch of screen. The mesh removes rubbish and if it is evident that there is a large volume of storm water in the sewerage this is passed into separate storm tanks.

The next stage is the removal of human waste – poo, food and solids from industry and farming etc., in what are called Primary Settlement Tanks (PST). The sewerage is separated out in large settlement tanks, where the solids or ‘sludge’ as it is called, sinks to the bottom. The amount of putrescible organic material in the sludge sewerage is indicated by the biochemical oxygen demand, or BOD. The higher the BOD, the more oxygen is required by micro-organisms to decompose the organic substances in the sewerage.

Then large arms or scrapers help to push the sludge towards the centre of the settlement tanks, from where it is pumped through the sludge valve to sludge tanks. It is then taken to Trowbridge for further treatment where, some of the sludge is recycled for farmers to use as fertiliser. Of what remains some will be used to generate electricity either by using a process called ‘anaerobic digestion’. That is, heating the sludge up to very high temperature, which encourages the bacteria inside to break down the waste, creating biogas to be burned to create heat that in turn, creates energy/electricity. Finally the remaining sludge is dried into blocks or cake that again can be burned to create energy/electricity.

The next stage of dealing with the sewerage at DMSTW are the Siphon Chambers that work on air and water levels. Once the cleaner water reaches a level, the siphon breaks causing it to go through the stone media trickle filters so that as it passes through, useful bacteria eats the harmful bacteria. The more the useful bacteria eat, the more they grow and multiply producing a biological solid in the form of sludge which is dealt with as described above. The remaining cleaner water is siphoned off to the third and final stage.

The cleaner water goes into the Humus Settlement Tanks (HSTs). These are the large round tanks that are often depicted in illustrations of sewerage works. Their job is to clarify the cleaner water by the removal of any solids that remain from sewerage, farming, industry, household waste and washing showers etc, which is resistant to microbial action. Hence the HSTs are equipped with air filters and work by slowly trickling the cleaner water through a bed of sand. Fine particles settle to the bottom of the tank (Humus sludge) which then goes to the sludge tank and then sent to Trowbridge for further treatment. Once dealt with it is highly prized as it contains many useful nutrients for healthy soil and favoured by gardeners!

The now clean water is tested to comply with the Environment Agency’s high quality standards and piped into the stream below the DMSTW. This is the stream that starts above Clearwood, crosses Stormore and then runs down the side of the deer fields in Dilton Marsh from south to north.

3. Dilton Marsh Water, Sewerage, Privatisation and Climate Change after 1970

The United Kingdom joined the European Community on 1 January 1973 when four Directives came into immediate effect, the first appertained to water resources and prescribed standards for the quality of drinking water. The second dealt with discharges of dangerous substances to the aquatic environment. The third, the quality of bathing water and the fourth the quality of fresh water for fish life. The government was ultimately responsible for ensuring that the Directives were codified into law and for ensuring that the respective standards were met. Each Directive required a significant programme of capital investment by each water authority.

Between 1972 and 1975 there was a colossal rise in the price of oil that increased inflationary pressures and effectively dictated how much investment could actually take place. Throughout, central government held on to its control of the water authorities by the introduction of the 1973 Water Act. This significantly reduced the number of water authorities to just ten, one of which was Wessex Water with the West Wiltshire Water Board ceasing to exist on 1 April 1974. These new water authorities could only raise money to finance requirements by borrowing from central government, which was difficult and/or from revenue received from customers.

On a practical level, the Act created an integrated river basin management system in relation to wastewater treatment. Wessex Water was faced with a combined system that had previously been subcontracted to a large number of different water authorities and reported that ‘half of our sewerage treatment works that we had inherited did not function.’ Following the introduction of an incomes policy in 1975, the inflationary pressures on the economy dropped but then rose sharply again in 1978 due to the combined effects of another sharp rise in the price of oil and also the increase of the expenditure tax, VAT from 8% to 15%. Further, most of the new Water authorities were plagued with relatively dry summers when they were forced to introduce hosepipe and sprinkler bans and on house building. In Dilton Marsh, Shepherds Mead, Greenacres, Friars Close and Clay Close together with general in-filling of housing throughout the village had taken place. Further there was an increase in the use of automatic washing machines, all of which were leading to increased pressure on the new sewerage system.

Between 1980 and 1986 the inflation rate fell by 15% and the decline would have been less without the VAT increase. Although the fall in inflation was said by some to be due to a fall in the dollar prices of the world’s primary products in the UK this had been offset by the rise in import prices due to sterling, which had continued to rise by 8-10% on the world markets. In fact the main cause for the fall in UK inflation was the rise in unemployment and the subsequent low pressure of consumer demand but this trend started to reverse in 1986. By the end of 1988 earnings were increasing by about 9½% per annum and a sharp rise in mortgage rates put a pressure on demand that ushered in an economic recession. Throughout this time the regional water authorities asked for but were declined help. Instead they received an onslaught from politicians and the media alike, particularly citing major internal conflicts of interest.

The water authorities, it was said, were not only in charge of water supply and sanitation, but also of water resources management. Hence, they were in charge of abstracting water and discharging wastewater so effectively policed both functions. Further, the Water Act had enabled the water authorities to contract out their services to local authorities and local authorities held the majority of board seats of the water authorities! In 1979, the new Thatcher Government aimed at making the water companies more commercial by making them more efficient and as a result the number of water authority employees were reduced by 19%. This decreased operating costs and at the same time investment was reduced and tariffs were increased. The number of board members was also reduced in the 1983 Water Act when local authority representation was abolished. Externally, the European Commission threatened the government with infraction proceedings over bathing and drinking water quality. At the local level, to meet new housing needs, Wessex Water managed to receive grants for the extension of water and sewerage structures in rural areas under the 1944 Rural Water Supplies and Sewerage Act. This enabled them to expand the DMSTW in 1982 and again in 1988.

Nonetheless, criticism of the regional water authorities continued to increase on the grounds that they were monopolies who used their dominance of the services they provided and the levies they charged by their own actions. In response, on 1 September 1989 Wessex Water Authority, along with the other water authorities became Public Limited Companies (privatised) through divestiture (sale of shares). That was with the exception of water resources management, which was retained by the public sector. Even though as providers of water related facilities the authorities remained intact, each one was separately listed on the British stock exchange thereby enabling the transfer of ownership of their shares from one body to another. The basic premise was the shareholders owned a share in the profits paid as dividends of the company and when the company wants more money they could offer a rights issue to shareholders. Thereby in theory competition is achieved by a company becoming more efficient and profitable which increases the dividend payouts. The prices water companies charge to customers was subjected to independent regulation. From the outset the premise was criticised, for although the regulatory authority appeared to negatively affect the individual water authority in favour of the consumer, as there are millions of consumers this still put the water authority in a strong position to seek favourable treatment by lobbying the regulatory authority. In consequence the Water Industry Act 1991 created the regulatory agency OFWAT as the economic regulator and Sir Ian Charles Rayner Byatt was appointed the Director General from 1989 a position he held until 2000.

For Wessex Water the increase in their finances by privatisation led to a dramatic increase in their capital investment and a £1.3 billion programmes of works was scheduled for the 1990s. In Dilton Marsh one of the concerns of consumers was the growing interest in the effects of Global Warming leading to flooding. Flooding had been a long term problem for the village. In May 1889, it was reported that a heavy thunderstorm was followed by heavy rain that caused flooding throughout the village. In July 1907 a thunderstorm lasting 4 hours and including a torrential downpour caused a number of properties to be flooded and this situation was repeated at an increased rate on a number of occasions until June 1930. That month it was reported that 1.03inches of rain fell in 45 minutes accompanied by hail that not only caused severe flooding but windows to be broken. The episodic flooding continued and following World War II national newspapers started to report incidents. For instance, the Manchester Guardian of 15 May 1949 told its readers that a localised thunderstorm flooded houses and shops in Westbury and surrounding villages.

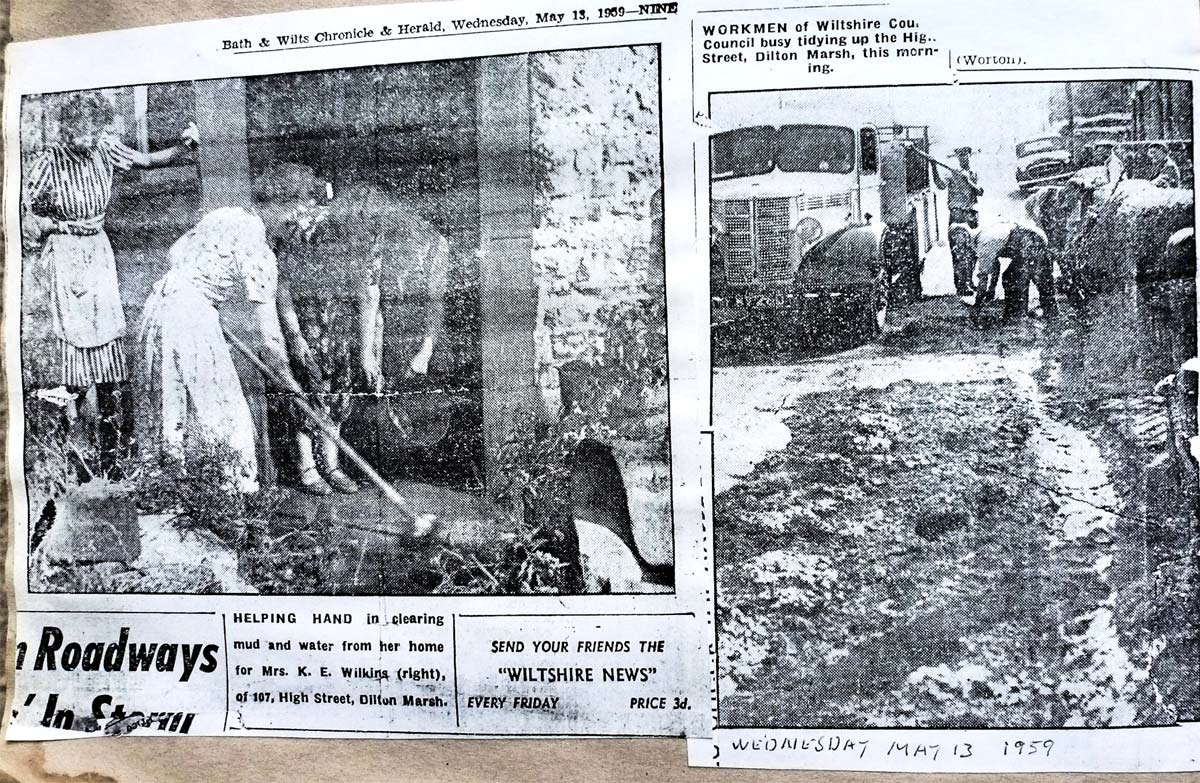

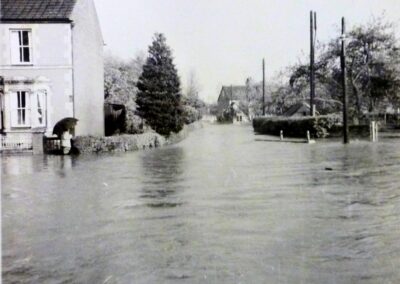

Then on 12 August 1954 these regular reports became more technical. That day the BBC reported that a trough of low pressure moved over the area bringing thunderstorms with 0.56 inches of rain falling in 10minutes. This led to homes being flooded and acres of farmland being under water in the Westbury area and a number of other places such as Upton Scudamore and Glastonbury. It was reported that in Dilton Marsh hay was seen floating down the High Street until late evening! Five years later, in May 1959 the Avenue in Dilton Marsh suffered flash flooding with water, it was reported, flowing down Park Road and the High Street. Before the month was out, the River Biss overflowed its banks close to the Apple Tree Inn flooding Penknap and again the resultant flooding made the national media but this time with photographs! In September 1992, two years after Wessex Water was privatised there was 4inches of rain in 24hours leading to deep flooding of properties particularly on the north side of the High Street and flash flooding along St Mary’s Lane, Stormore, Clearwood and the bottom of Clivey Hill.

While householders insurance companies paid out for damage caused by the flooding, the residents were faced with higher insurance bills and their anger turned on the Water Company. To avert further flooding Wessex Water promised to clear Dilton Marsh drains and at OFWAT Ian Byatt imposed a substantial price reduction on private water companies for their inefficiencies and high dividends. This had the effect of substantially reducing the privatised water companies share prices that aroused foreign interests. In 1992 the Competition and Service (Utilities) Act was introduced that increased OFWAT’s powers to determine disputes and increased the limited opportunities for competition in the industry.The following year, 1993, at a cost of £133million Wessex Water went into partnership with Waste Management International, headquartered in the Bank of America Tower in Houston Texas, to form the subsidiary Wessex Waste Management. The following year Wessex Water reported that the move had secured a doubling of their profits to £9.1 million adding that Wessex Waste Management had 100million cubic metres of landfill sites in Sussex, Humberside, Cheshire and North Yorkshire. Albeit, their performance judged on profits was seen as relatively poor and the price of their shares fell dramatically on the London stock exchange.

The 1995 Environment Act led to restructuring of environmental regulation and placed a duty on the companies to promote the efficient use of water by customers. The Act also created a new body, the Environment Agency, which took over the functions of the National Rivers Authority along with Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution, the waste regulation functions of local authorities and certain elements of the Department of the Environment. That year a BBC Panorama programme reported that a number of privatised water companies had increased their profits to more than £6.5billion by leaving unspent some £200million intended to be used on renewing sewers. Wessex Water came under the spotlight with Colin Skellett named as the managing director of the Company. He said that ‘due to other priorities the money earmarked for sewer renovation, such as sewer flooding and pollution incidents but the situation was changing.’

Following the airing of the programme the company cut operating costs by 45% and made 30 senior executives redundant. The next year a confident Wessex Water made a bid for South West Water but this was vetoed by the Government on the grounds that the merger would reduce the number of British water companies. Before the year was out, Wessex Water launched a share capital-restructuring programme that included buying back most of the shares held by Waste Management International. This cost them about £24million with the Chairman, Nicholas Hood, saying that the move would ‘increase earnings per share, improve the company’s ability to pay increased dividends per share and to simplify the capital structure’ (Times 19.12.1996 p22).

Legislation of the water companies increased in 1998 when the Competition Act prohibited any agreements between businesses that prevents, restricts or distorts competition and also prohibits any abuse of a dominant market position. The enforcement powers were shared by OFWAT in relation to the water and sewerage sectors with the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). That year it became illegal to dump sewerage sludge at sea and Wessex Water continued to promise that works to ameliorate sewerage problems would be undertaken. Then on 24 July 1998, the American energy, commodities, and services company Enron International, based in Houston, Texas, made an unexpected cash bid for Wessex Water from its shareholders for £1.36billion. This was the same amount as Wessex Water had said they planned to invest in a programme of works back in 1989! The Financial Times reported that Nicholas Hood received £1.2million and Colin Skellett £1million. The then Trade and Industry Secretary Peter Mandelson gave approval in September 1998. Enron assured Mandelson that Wessex Water would be ring fenced from the rest of its companies and accepted that Ian Byatt, Director General of Water Services, would regulate the company.

Within a month Wessex Water was renamed Azurix floated on the New York stock exchange and named as Enron’s international core asset as it planned to expand to control other water companies. In May 1999 Azurix/Wessex Water, was reported as being the most successful and profitable water utility in the country, at the time its shares were selling at $23.8 each. Still referred to as Wessex Water, Ian Byatt imposed a 17.5% mandatory price cut to consumers over which Wessex Water appealed. The price cut was reduced to 12% with the proviso that from April 2000 the company would upgrade the utility’s ageing infrastructure. This was estimated to cost over a billion dollars. In the meantime, the 1999 Water Industry Act looked at the power and responsibilities of the privatised water and sewerage companies including removing a company’s right to disconnect domestic customers for non-payment of bills. Limiting the circumstances in which companies can start charging domestic customers on a metered basis and securing what companies could continue to charge customers on the basis of rateable value. At Enron’s headquarters the assumption that Azurix/Wessex Water would provide the base for major expansion in the British water/sewerage industry and also the power and energy industries was proving frustrating and costly.

By the autumn of 2000, Azurix/Wessex Water shares had fallen to under $4 each and by the end of that year the company was $2billion in debt. In the US, Enron the company’s earnings were also falling then in October 2001 they were forced to write off a $1.2billion debt run up by a none consolidated partnership by the finance director. This was compounded by fudging the purpose and liabilities of these off-balance sheet figures that had, from 1997, appeared as cumulative profits of $580m. The company tottered then on 29 November 2001 the European division of Enron collapsed into administration. Although in the UK such secret accounting practises were illegal, the collapse of the parent company put 1,400 jobs at Wessex Water and the British power and energy industries in jeopardy. Further, approximately 150,000 British homes and businesses used Enron Gas and electricity. The British labour government was quick to make assurances but came under attack over its original approval of the Enron take over of Wessex Water.

On 25 March 2002 Wessex Water was bought by the Malaysian Group, YTL (Yeoh Tiong Lay) Power in a £1.24billion deal that included paying £545m for the company and assuming its £695m debt. YTL announced that they were leaving the current management in control of Wessex Water and that the company provided approximately 1.2million people with drinking water in more than 500,000 properties and sewerage services to approximately 2.5million people. That year the 2002 Enterprise Act amended the Water Industry Act 1991 to update the regime for the compulsory reference of certain mergers between water companies to the Competition Commission (since 2013 the Competition and Markets Authority). In the following year the 2003 Water Act was introduced to amend the framework for abstraction licensing, making changes to the corporate structure of economic regulation and extended the scope for competition in the industry to large users.

Nationally, the Committee on Climate Change predicted that demand for water in England would be greater by the 2050s than the predicted available supply of between 1.1 and 3.1 billion litres per day. This, was despite a significant increase in demand due to house building, the general use of non-porous materials used on roads pavements and driveways, automatic washing machines, dishwashers etc and due to mismanagement the loss of approximately 3 billion litres of water (20% of total supply), due to pipe leakage’s. They also pointed out that no substantial reservoir had been built in England since the Kielder Water dam in Northumberland in 1981.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed that new housing supply had increased year-on-year from a low point of 125,000 in 2012/13 to a high point of 243,000 new homes in 2019. This, according to the Environment Agency had reduced the country’s amount of green space and together with climate change a growing population was increasing the risk of floods. They went on to say that extreme weather events were four times more likely to happen than in 1970. Adding that since 1910, there had been 17 record-breaking months of rainfall and nine of these have been since the year 2000. In Wiltshire in 2015 approximately 500 homes were flooded and a number of schemes were introduced or extended, including a Council Tax Relief Scheme, supporting councils to provide council tax rebates to residents whose homes were flooded. The Business Rates Relief Scheme that supported local councils to provide business rates rebates to those premises that were flooded. Severe Weather Recovery Scheme (communities’ element) to support local authorities with the costs associated with impacts on local communities. Repair and Renew that provides grants of up to £5,000 for flooded homeowners and businesses to improve the resilience of their properties; and the Business Support Scheme, that provides hardship funding to businesses affected by the floods.

In early 2023, the Environmental Agency produced summary reports on the highest risk from surface water flooding within a 15-metre radius of properties. This can be seen on the internet and provides for categories: High Risk, which means that the area has a chance of flooding of greater than 3.3% each year; Medium Risk where the area has a chance of flooding of between 1% and 3.3% each year; Low Risk and the area has a chance of flooding of between 0.1% and 1% each year and finally Very Low Risk where the chance of flooding of less than 0.1% each year. Although the Agency states that it is very unlikely to be reliable for a local area and extremely unlikely to be reliable for identifying individual properties at risk the results does provide wake-up calls. For instance, the Red Cross has found that to repair a flooded home is estimated to cost £30,000 and further, more than two-thirds (70%) of UK adults admit that nobody in their household has taken steps to prepare for floods. An analysis of homes in Dilton Marsh for this essay, using Environmental Agency data, implies that 11.9% of village properties are classed as High Risk of being flooded.

Lorraine Sencicle 2023

With thanks to:

Wessex Water – particularly DM Sewerage Treatment Works, Clivey, Dilton Marsh especially Keith Tabley,

Wessex Water – Customer Relations especially Alan Pippett

Wiltshire Council Operational Planning, Economic Development & Planning especially Mrs P Broom

Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre

Westbury Library and Museum

Trowbridge Museum

DEFRA

Environmental Agency

Tait ap Ellis White Horse News

Deborah Urch, Westbury Town Council

Nicola Duke, Dilton Marsh Parish Council

Valerie Headland, Dilton Marsh Local History Society

Mike Hyde of Dilton Marsh

1959.05.13 Flooding cleaning up 107 High Street & Wiltshire council workmen ‘tidying up’ the High Sreet

1959.05.13 Flooding cleaning up 107 High Street & Wiltshire council workmen ‘tidying up’ the High Sreet